SPACE

SAUZET

AND

CARBALLAR

ARCHITECTS

The Theory

To derive satisfaction from any given architecture, it is essential that one's relationship to one's habitat be based on quality. It is a subtle relationship not limited to rational facts. How this quality is perceived varies through cultures and time.

Today, in Western Europe, the relationship to the nature of things and to human nature has become all-important. This relationship will remain impossible as long as architectural dogma is maintained.

Natural Architecture, that is to say an architecture that makes use of methods that are apropriate, has the ability to arouse in us a powerful relationship to our environment, instantly experienced as a thing of beauty.

The Method

In the design stage, the designer must be able to assess the quality of the relationship between man and space for each individual place. In any building, specific sequences of movement operate, between entrance hall and living room, bedrooms and kitchen. These are the paths that underscore daily life, and they give rise to the concept of main pathway. Each and every occupier is bound to follow it as it takes him from the immediate outskirts of a building to its very core. Schools, town halls, offices, hotels are all subject to these inescapable sequences of movement.

Seven key concepts sum up our method :

- Conceptualising pathways

- Kinaesthesia

- The framing of views

- Counter-spaces

- Conceptualising depth

- The treatment of boundaries

- Transparency and veiled views

Conceptualising pathways

Plans are drawn up with a view to enhancing the occupier's ambulatory experience. In other words, the positioning of doors and passages on a plan creates a succession of spaces. These succeeding situations will be subject to new requirements and no longer to functional constraints.

Such requirements liken these case studies to the processes of film editing; each sequence needs to hold interest in the moment whilst being part of a totality. The type of sensations one experiences is based on the amount of coherence or contrast within these sequences.

By virtue of this second founding principle, the ambulatory experience must enable a relationship of the highest order between man and the outside world; on the one hand, via an awakening of the senses, on the other hand, via the quality of the representations of the world, which are highlighted. Rough surfaces, elements to grip on to: these give our senses the opportunity to seize the World. Our presence, in the here and now, will take effect with unsuspected force.

Kinaesthesia

The aim is to associate a movement induced in the body with an exterior perception. Resorting to this type of physical signature was not unknown to classical architecture: there is a bit of climb leading up to holy places or authoritative monuments.

This is used extensively in Japan: doors are too low, forcing one to duck; door sills exaggeratedly high, forcing one to lift one's leg. Deliberate obstacles are used to create detours. An abutment at the junction of two paths will force one to make the obvious choice.

To transpose this to our contemporary world requires sound judgement. One must be aware of the point beyond which excessive stimulation becomes a hindrance. The act of lifting one's leg will be associated with the need to ascend. Conversely, gently sloping paths leading to a given space, small mounds forcing one to circumvent the garden, will frequently be used in the mise en scène of the place.

What is the purpose of such devices? To awaken our being! To awaken us to our presence in the here and now! To escape automation, to eschew the all-pervading pull towards uniformity. By associating an unusual gesture with the discovery of a given place, we create a physical imprint that our body memorizes.

The Framing of views

Classical art has accustomed us to set windows and openings in accordance with the rhythms and dimensions visible on the front of a building. Modern architecture did not overtly turn away from this relationship. It did not, as far as openings are concerned, try to find a role for them within a harmonious relationship between the inside of a building and the outside world.

Conversely, Japan, with its unshakeable connection to nature, did not develop the principle of linking windows to façades. Houses, temples, monasteries are all shelters allowing one to participate in one's environment. The need to protect oneself against the harshness of the climate gave rise to the shojis, sliding door frames with paper stretched over them, and to protective wood partitions, put up in times of great necessity.

But the wide openings between the walls normally remain completely open. The lateral partitions and the large overhanging roofs frame the gardens and the distant landscape just as a painting would. Some of the narrow openings, only a few centimeters high, can be pulled open to reveal, at floor level, leaning against the partition, a perfectly framed flower growing outside.

This process translates directly into the European tradition. Windows, mere elements on the façade, are discarded in favour of openings positioned so as to match the surrounding landscape and enhance the interior-exterior relationship. In bedrooms, as the bed stays in the same spot, a relationship needs to be established between optimal view, the opening in the wall and the positioning of the bed in the room.

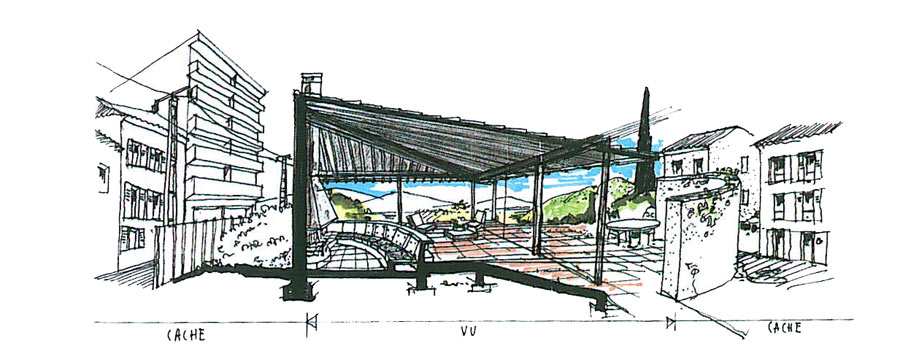

Framing of views in a cluttered environment

For the outward appearance of the construction, we have found other ways of creating harmony besides resorting to the rhythm of the openings :

The framing of views has other virtues. It can help discard any element that does not fit into the landscape: electrical pillars, neighbouring houses, etc. Sometimes we need to add accompanying objects to the area of the garden that we control - trees for instance - so as to reframe what can be seen on the horizon.

This effort to control the surrounding views can go as far as creating exterior walls to screen out unwanted elements. They will hide any views that are either unpleasant or intrusive and will replace them with a contained and well arranged landscape.

Bedroom with concealed-frame glazing, opening onto the sea

Counter-spaces

These new relationships created between the inside and the outside world, demand that we forge a new concept. Given such strong continuity between interior and exterior, the character of the adjacent exterior surfaces will be dependent on this relationship. We use the term « counter-spaces » to describe this process.

The bathroom will require a thoroughly exclusive « counter-space ». In most cases, it will be a garden that is inaccessible save for gardening. The same applies to a toilet. For bedrooms offering distant views, we make use of counter-spaces which are hard to access and which open up onto the horizon.

The Conceptualization of depth

The notion of depth is particularly valid for buildings with vast openings. Here, light penetrating deep into the building, gardens nestling in the heart of intimacy create the opposite need: the need for protection.

In Japan, the techniques used to create distance within confined spaces are unique. They introduce directional breaks and create succeeding thresholds. Breaks, changes in direction, crossings that have a strong impact on the senses and that are disorienting, all create an impression of distance which has little to do with the mere physical distance separating one point from another.

We have translated these same methods into our own architectural language.

The Treatment of boundaries

In contrast to our own culture, with its emphasis on endings and beginnings, on giving each individual room a definite outline, the culture of Tao does not set extremes in opposition to each other but associates them. This applies to endings and beginnings. In Japan, the emphasis is on transitions, elements of continuity, associations. This self-effacing technique is used with particular sophistication when linking the interior and exterior of the main halls of temples. As places of worship, they need to make the congregation part of a continuum between outdoors and indoors, nature and shelter. This supreme space must bring to the fore the unshakeable bond between man and nature. Large overhanging eaves take possession of a vast exterior space. Conversely, the garden is afforded protection against profanation.

The type of architecture we are concerned with makes great use of these tools in addressing boundaries. They are used to regulate one's relationship with the outside world. In some cases, they conceal the link, in others, they apply limiting filters to it. In most cases, this architecture will avoid imposing sudden breaks in the views or walkways.

In the living room we find the greatest scope for contrast; one area will have to offer sheltered depths, whereas others will need to open up to the incursion of the outside world.

All the threads that weave a visual barrier between the interior and the exterior world get unravelled. By dissociating them, we are able to split up and negate all boundaries, by the use of :

- continuous flooring between indoors and outdoors

- glazed doors with concealed frames

- shifting structures in relation to the glazing

- strongly jutting out eaves to create unusual shadows

- gardens extending across the interior-exterior boundaries via glazing

With bathrooms, this continuity between the interior and the exterior holds particular appeal. An enclosure of privacy is added. This enclosed garden brings about another counter-space, in effect doubling the size of the room. Walls are at eye level, allowing one to glimpse yet not see; to be protected yet not imprisoned.

Transparency and veiled views

These act as strong undercurrents releasing the power of our imagination. They have not been neglected in our culture: the shadows cast by churches, the transparent veils covering human nudity. But contemporary architecture, more prone to objectivity than flights of imagination, has completely forgotten them.

The architecture we are concerned with, makes lavish use of them : walls that stop at eye-level, halfway between showing and hiding, deep and lengthy shadows (see In Praise of Shadows by Tanizaki) and screens. The latter are the tool of choice for creating « half-views ». Screens have a great many uses. These vary in accordance with the shape and thickness of the screen. Horizontal screens enable shifting « half-views ». Vertical screens create frontal views that are veiled. They become laterally impenetrable. Square screens are more classical. Frosted glass, akin to stretched paper, diffuses opalescent light. It comes alive with falling shadows, opening the doors to the imaginary world.

Copyright © 2011-2026 - Developed by Gayar Ti' Tang